Today we’ve got you one incredible article from my friend Jon Hodges of Nevada PT. Whether you are a coach, clinician, or just someone who has ever been injured, you’ve likely heard about adhesions. Shocker – what you’ve been told about them is probably not quite so accurate. Let’s learn why!

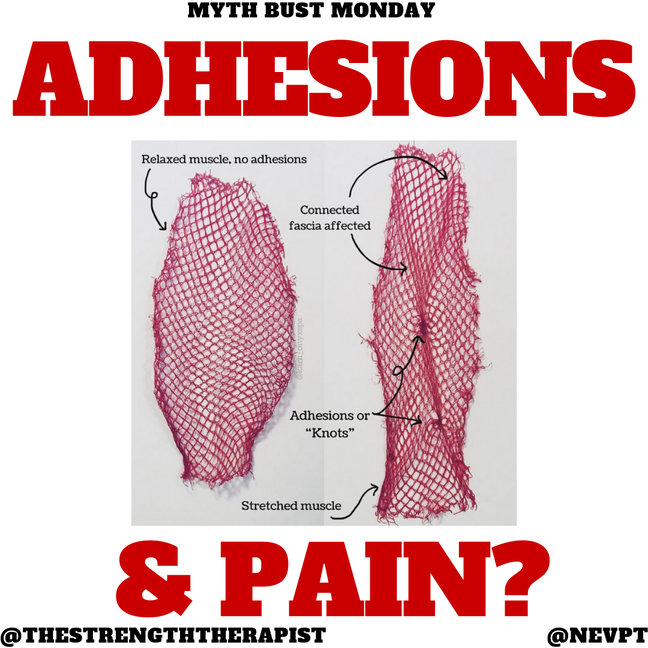

Adhesions have commonly been used as an explanation for the source of an individual’s pain, loss of mobility, etc. going so far as this website calling it “possibly the most common musculo-skeletal pathology in existence”.

Subsequently, this has spawned countless treatment systems used to address these alleged patho-anatomical anomalies.but where did this come from? Do adhesions even exist?

Img Credit – https://lmimirror3pvr.azureedge.net/static/media/13242/d9c78537-01f6-4b4c-8bde-e03eccf8db2a/fp_foamrolling_960x540.jpg

Greg Lehman remarks on the topic comparing them to the classic chiropractic myth of vertebral subluxations, “Believe it or not there is more research behind subluxation than there is behind an adhesion”.

There are two primary definitions used for the purpose of this discussion. The first is an atypical fibrous connection between the fascia and muscular layers or “myofascial adhesions.” If you have seen Gil Hedley’s infamous video, it’s enough to make you believe you need to do spinning roundhouse kicks in the morning just to prevent the “fuzz” from building up.

Paul Ingraham breaks down that video over at PainScience.com better than I ever can for those interested. The other definition will be aberrant fibrotic development in the muscle or “muscular fibrosis.” We’ll throw scar tissue in for good measure as well.

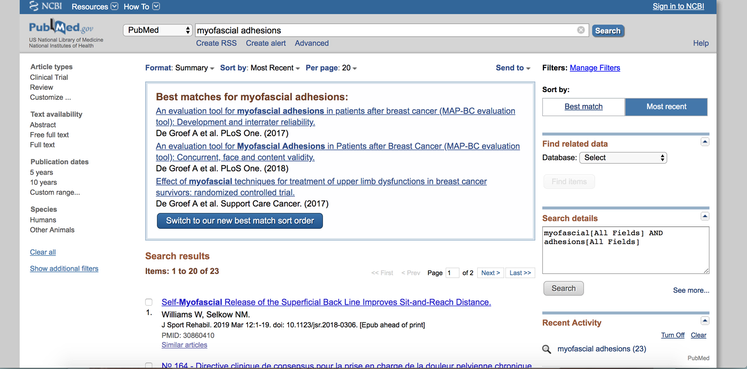

The fear of adhesions has been routinely established in the rehab and fitness industries, but what does the literature say? A Pubmed search of “myofascial adhesions” revealed 23 findings in total.

Not one of the 23 studies established the presence of adhesions outside of surgical trauma or pathology. We do see post-surgical adhesions in the tendon sheath after surgical repair in the hand (Wong et al., 2009); adhesions in the intra-abdominal cavity after abdominal surgeries or trauma (Beyene et al, 2015), and we see adhesions in potential genetic disorders (Wiseman, 2008) – there is even a case report showing interosseous-lumbrical adhesions after a cat bite infection (Muder & Vadung, 2014).

https://akm-img-a-in.tosshub.com/indiatoday/images/story/201501/catstory_650_010615030200.jpg

In fact, non-traumatic adhesions appear to be so unusual, there was a need to publish a case report on the “anatomical variant” of adhesions in the bicep tendon to the undersurface of the rotator cuff (Hammond & Bryant, 2014). Which, by the way, they attributed to a traumatic event. Not one published paper could be found on the presence of myofascial adhesions in any other scenario, let alone the usual exercise mechanisms sold by practitioners.

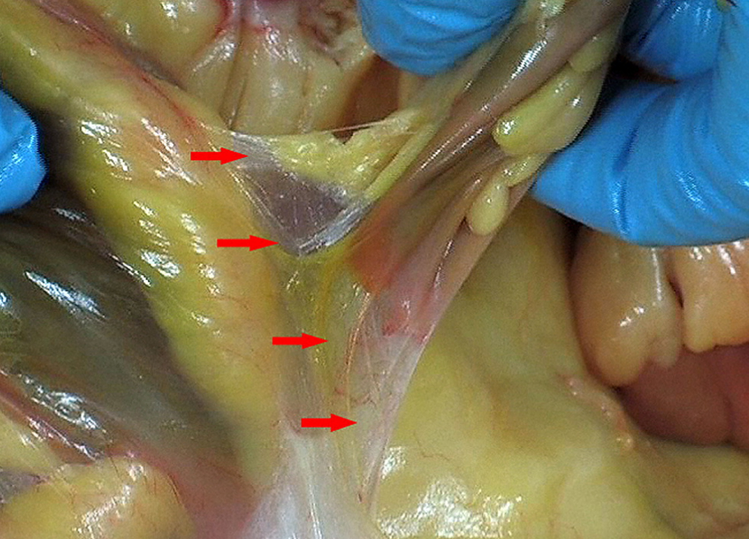

Image source: Notes on Visceral Adhesions, Hedley, 2010

While there are no studies, that I could find, that showed the presence of myofascial adhesions in non-traumatic or non-pathological conditions, they do continue to be referenced. Take Salvi Shah for example who says

“Structures that were originally designed to be functionally separate will form adhesions which will impair their ability to slide freely over one another…”

but alas, the only reference is to a textbook from 1991 on Myofascial Release by Regi Boehme (a pupil of John F. Barnes, the founder of www.myofascialrelease.com and self-claimed “icon” in healthcare therapy-also the guy that served a cease and desist and threatened to sue several well-respected evidence-based clinicians for posting scientific evidence refuting his claims back in 2008).

Img Credit – https://www.myofascialrelease.com/images/merchandise/books/mfr_sfe_cover.jpg

The Salvi Shah publication is, incidentally, listed as one of the top 10 cited articles on http://www.ijhsr.org/. A word of caution, do not visit that website if you have any visually-induced seizure disorders or are currently suffering from a migraine.Similarly, Gil Hedley’s “Notes on Visceral Adhesions as Fascial Pathology” paper (2010) is also worth mentioning because while he presents many fascinating dissection photos, there are no literary references regarding insidious adhesion formation here either, other than “in the author’s experience”. In fact, of the 16 references in his publication, only 6 are scientific papers published in literary journals, 4 are references to Hedley’s own DVD series. Yes, DVDs.

If we venture outside of published scientific literature (a fool’s errand admittedly), we see how this concept of myofascial adhesions is perpetuated in the industry despite the paucity of actual scientific support. Expanding my search, I came across a Masters of Exercise Science thesis presentation by Fama and Bueti (2011) in which they reported “when irritated, the fibrous tissue forms adhesions, decreases compliance of the fascia, limiting circulation through the underlying tissue and inhibit function due to ischemia” which, surprisingly does have a few references attached.

Img credit – https://memegenerator.net/img/instances/65851783.jpg

The first, an article by Vernon & Schneider (2009), and second, an article by Holt and Lambourne (2008), upon review neither ever mention adhesions, the latter does not even mention fascia.

Curran et al. (2008) in their article about foam rolling, state “injuries stimulate the development of inelastic, fibrous adhesions between the layers of the myofascial system that prevent normal muscle mechanics and decrease soft-tissue extensibility” with a reference attached. That reference? A textbook on Myofascial release. I could go on as this pattern is simply repeated with many references for citations being either articles that never mention them, textbooks, or “experience”.

It would appear that while there are many references to adhesions, there appear to be very few published studies on the presence of myofascial adhesions outside of trauma, surgical intervention, or pathology. In fact, I could not find a single one. What about scar tissue then? It seems the common argument for many of these trademarked interventions is to break up “adhesions or scar tissue” in the muscles and fascia.

Baoge et al. describe the scarring process in more detail:

A few things stand out: tearing of blood vessels and scar tissue being needed to restore mechanical properties of the muscle fiber unit. It would appear that the “microtrauma” argument made from chronic exercise may fall short of the tearing of blood vessels seen in the induction of scar tissue formation. It should be noted that after 10 days, the scar tissue is actually stronger than the muscle unit and any future tearing happens within the muscle fiber itself (Jarvinen et al., 2005).

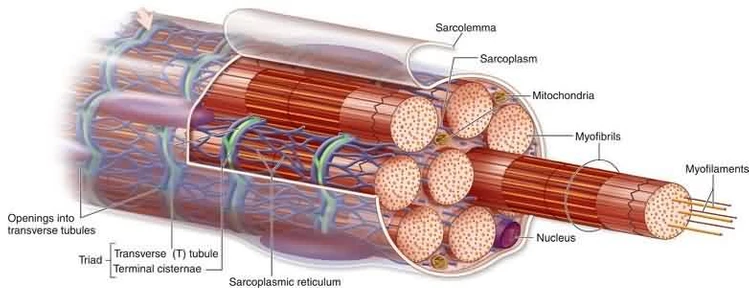

Img Credit – http://otteastbourne.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/OTTEastbourne_Post_operative_scar_tissue_soft_tissue_therapy_muscle_structure.jpg

So it would appear that we need: 1) a trauma of the magnitude to rupture blood vessels to induce scar tissue formation in most cases, 2) scar tissue is needed to restore the mechanical integrity of the force-production capabilities of these muscles, and 3) scar tissue is normal and necessary in the healing of injured muscle and any intervention to disrupt that may actually be counter-productive in the first 10 days and beyond that, we are more likely to damage the muscle fiber than the scar tissue. What about chronic microtrauma and/or inflammation? A quick search on “chronic exercise and adhesions” yielded 0 results on pubmed. However, interestingly, it would seem exercise is actually a potential treatment for chronic inflammation as Gleeson et al. (2011) state:

Additionally, a Pubmed search of “chronic exercise and scar tissue” yields 32 results – yet only one from 2001 (Weldon et al.) actually mentions exercise. However, the “scarring” they describe goes unreferenced. That being said, while it is established in the literature that pathological inflammation can create fibrotic development, this discussion seeks to establish if there is any validity to the concept that exercise is a mechanism for this fibrosis pathway. Wynn and Ramilingham (2012) list many of the causes of this pathway including:

While not an exhaustive list, chronic exercise is never mentioned. Interestingly, they conclude with the “need to begin viewing fibrosis as a pathological process distinct from inflammation”.

The jump in logic in our industry seems to be that inflammation is equal to the mechanism for fibrosis development which does not seem to be well-supported in the literature. *Sam’s Note – comically, for a good portion of the causes, we see exercise being a treatment intervention to reduce the impact of those conditions.

Img Credit -https://article.images.consumerreports.org/prod/content/dam/CRO%20Images%202019/Magazine/January/CR-Magazine-January-2019-Treadmills-Main-1116

Chronic exercise, specifically, does not seem to check this box. In fact, investigating exercise itself, we actually see it as a mechanism for anti-inflammation as established by Peterson et al. (2005) who report:

And:

Further, they conclude that their investigation:

While we have established mechanisms of both scar tissue formation and muscular fibrosis, there seems to be no evidential support for exercise, even chronic exercise, as a condition that would drive this pathway. While muscular fibrosis is noted in those with muscular dystrophies and in the aging population (Mann et al., 2011) the treatment is actually, wait for it, EXERCISE (Horii et al, 2018).